Today (Tuesday 21 May) a new exhibition Kings and Scribes: The Birth of a Nation opens at Winchester Cathedral.

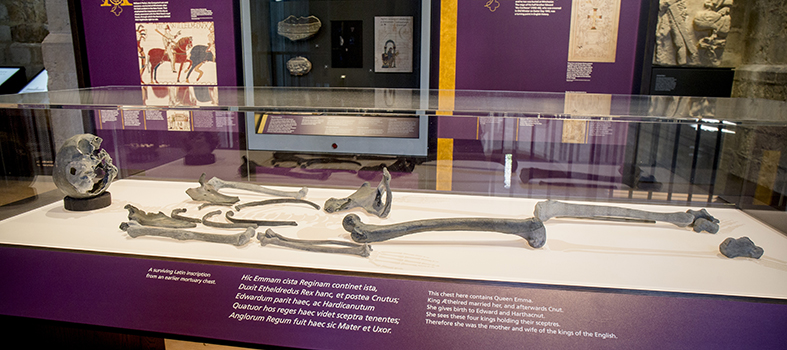

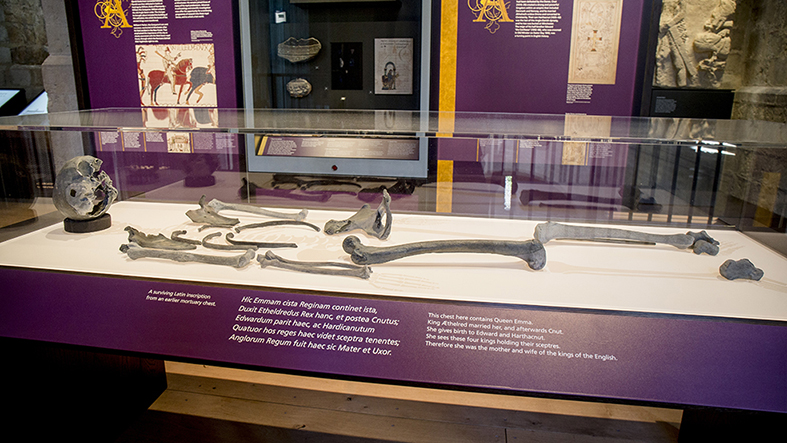

The exhibition presents some findings from a research project led by the University of Bristol to analyse the human bones from six Winchester Cathedral mortuary chests thought to contain the remains of an Anglo-Saxon Queen alongside several Anglo-Saxon Kings and Bishops. These remains had become commingled over the centuries so that no one individual is contained within any one chest.

In our latest blog post, Dr Heidi Dawson-Hobbis, a biological anthropologist who worked on the project to analyse the bones, gives an insight into how researchers are piecing together history and the identities of the individuals contained in the chests.

As a biological anthropologist my role in this research project has been to record and analyse these human remains, which consist of over 1300 separate bones, and to try and re-associate these bone elements to individuals with the hope of finding out who they were.

This work took place within the Lady Chapel at the Cathedral, which became a temporary laboratory.

This was an unusual space in which to find myself working, being more used to carrying out skeletal analyses in university laboratories. This, of course, presented its own challenges in terms of the lighting and equipment available, but it was an amazing space to call 'the office' for my time working on the remains.

As each chest was opened, we accurately recorded every bone through photography and drawn plans and allocated each one a separate number. Therefore, if we were required to restore the bones from the chests to their original positions, we could do so. We recorded all the information we could about each bone on a separate form. This included assigning an age-at-death, a sex, estimating stature from long bone lengths (for example, a femur in the leg or a radius in the arm), and recording any pathological and genetic anomalies.

After all the elements were recorded, our aim was to try and re-associate each bone to others to create individual skeletons. To do this I used morphological assessment, using the individual variation that humans have across their skeletons, by comparing each of the left and right side bones looking for a match.

I started by literally laying out all the hip bones on tables and working through them to find matches. From this bone, I could work from the hip joint to articulate each leg and then from the sacrum in the lower back upwards to try and articulate the vertebral column. This also involved metrical analysis and statistical work to determine if these matches made a 'good fit'. Once the remains were re-associated I could begin to build up a biography for each of the individuals contained within the collection, and compare this information with historical information we had for those individuals thought to be contained within the chests.

Our early findings have identified at least 23 separate individuals, two of which feature in the Cathedral exhibition.

Replica bones of the female skeleton displayed in the exhibition. Image courtesy Winchester Cathedral.

One of these partial skeletons is a female of mature age. As the only female that appears to be represented in the chests and with a radiocarbon date that places her within the Anglo-Saxon period she could be Queen Emma, wife of King Ethelred and Cnut and mother of King Edward the Confessor and King Hardacnut.

From the names on the mortuary chests, I expected there to be a majority of adult male skeletons represented, so it was a surprise when opening one of the mortuary chests to have the skull of a child staring back at me. In fact, the near complete skeletons of two adolescent boys aged between 10-15 years were found contained across multiple chests. Radiocarbon dating suggests they are from the early Norman period and historical work is on-going to find suitable candidates for who they may be. My PhD research was based on children from the late medieval period so I was delighted to be able to use my skills in developmental osteology to re-associate the bones of these two children, one of which features in the exhibition.

Dr Heidi Dawson-Hobbis (left) at the exhibition. Image copyright: Hampshire Chronicle.

At the start of this project, I had my reservations that the remains in the chests would be as old as purported. However, having analysed the collection, and with the results of the radiocarbon dates placing the remains in the Anglo-Saxon and early Norman periods, we are now confident that they do represent a collection of high status individuals whose bones have been carefully curated over the centuries by their custodians at the Cathedral.

I was delighted when the Cathedral decided that they would like to focus on the female and one of the children for the opening of the exhibition. If the female remains are of Queen Emma -and of course any interpretation is tentative at this stage based on the available evidence - she was an important woman and a powerful political figure in her own right. So often in historical texts, women's lives and roles are neglected, so to have a female at the forefront of the exhibition is exciting.

The two children are more of a mystery that we are continuing to investigate further. I hope that the focus on children from the past and allowing visitors to come face to face with one of them as part of the exhibition will help engage children and schools with the history showcased by the exhibition.

Dr Heidi Dawson-Hobbis worked on this project as a research associate at the University of Bristol. She is currently a Lecturer in Biological Anthropology at the University of Winchester and Programme Leader for the MSc in Human Osteology and Funerary Studies.

Press Office | +44 (0)1962 827678 | press@winchester.ac.uk | www.twitter.com/_UoWNews

Back to media centre