A new paper commissioned for the Centre for English Identity and Politics looks at the marginal seats in England that will form the battleground for the next General Election. Lewis Baston highlights where Labour will need to extend its appeal, and where the Conservatives have the best chance of regaining seats.

The focus on England is deliberate. UK governments are, of course, formed by the largest UK party (with, if necessary, the support of minor parties), but the politics of the four nations have quite distinct features: they have distinct national issues, are contested by different parties and, in recent years, have been won by different parties. Although the Conservatives’ current position would have been much more precarious without its gains in Scotland, neither of the two major parties have recently been able to rely on a secure level of representation from Scotland to ensure a working UK majority.

England is also gradually being recognised as a distinct political identity. The Conservative government introduced English Votes for English Laws in the Commons, and Labour is committed to a Minister for England, a constitutional convention that would consider a federal UK, and ‘a relationship of equals’ between England, Wales and Scotland. ‘English interests’ emerged as a distinct election issue in 2015 when it appeared that the SNP might support a minority Labour government.

For these reasons the outcome of future General Elections in England is likely to assume more importance than is formally required constitutionally. Both major parties may need to secure an English majority to win a UK majority, and the legitimacy of any government that does not have an English majority may be questioned by English voters.

The electoral map of Wales and Scotland has become a bit friendlier to Labour than the harsh results of the 2015 election, but it is the situation has not been restored to the previous era in which Welsh and Scottish seats were a cushion that allowed Labour to get away with underperforming in England.

The only secure route to a Labour majority in the UK is for Labour to win in England. The Conservatives, too, cannot rely on further Scottish gains and their future majority lies in England. Historically, outright Labour general election victories in England are rare. There have been only four occasions when the party scored an unambiguous victory, with a lead in the popular vote and an overall majority of English seats – 1945, 1966, 1997 and 2001.

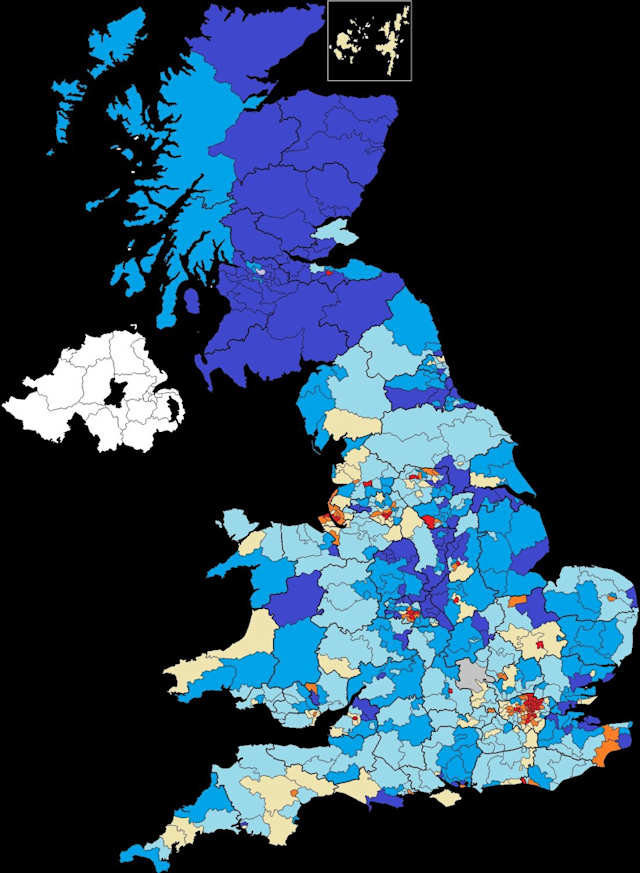

A striking feature of the analysis is the changing electoral geography of England. As Labour gains younger, more middle class and cosmopolitan voters, and the Conservatives attract older working class voters (and as demographic, social and economic change continues to reshape towns and cities), new seats come into contention. Former marginals become relatively safe seats for one party or the other.

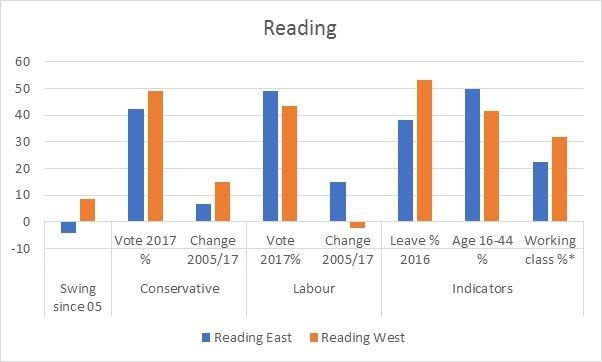

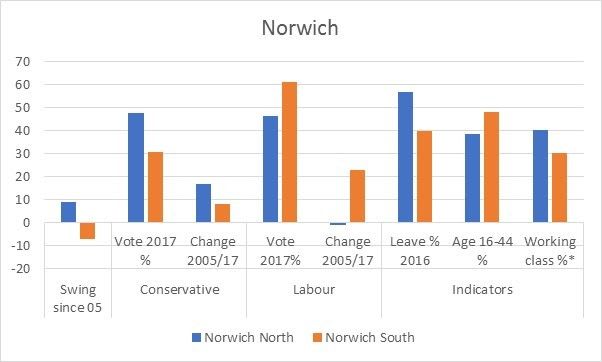

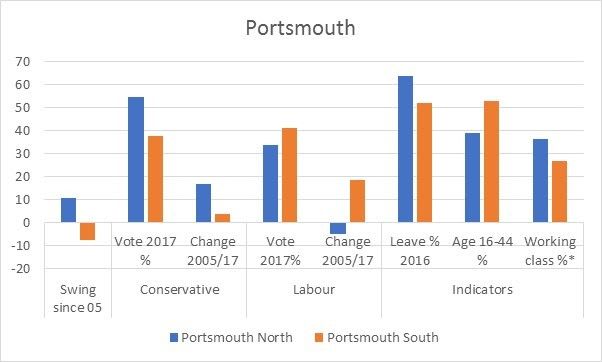

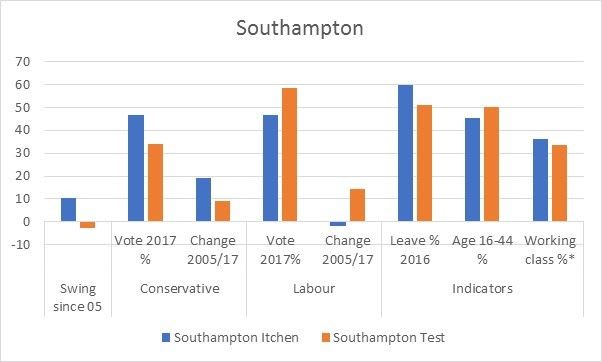

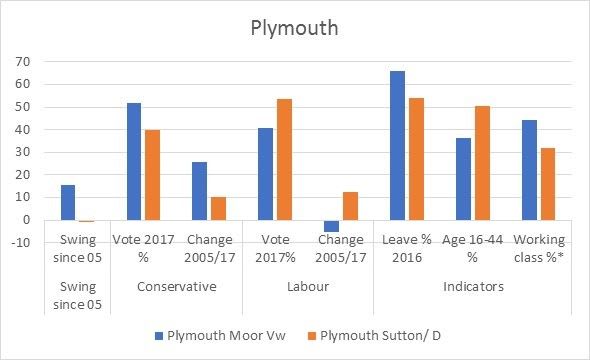

This trend is illustrated by five southern cities: Reading, Norwich, Portsmouth, Southampton and Plymouth. In each of these cities there is a startling contrast between its two parliamentary seats. In the younger, less working class and less pro-Leave constituency, Labour has improved its position by more than the Conservatives, gaining two from the Conservatives since 2005 (Portsmouth South, Reading East). In the other constituency in each city, the Conservative vote share has risen massively while Labour’s has declined, in each case causing the seat to flip from Labour in 2005 to Conservative in 2017. In most of these cases the more working class half of the city had enjoyed a longer and more consistent Labour tradition than the seat that Labour now represents.

The key battlegrounds at the next election will be in large towns and small cities across England. They tend to be more strongly ‘Leave’ constituencies than the metropolitan cities and university towns where Labour polled so strongly in 2017. There are only a few of the high Leave vote, ageing white working-class constituencies and small town, ex-industrial Midlands seats where Labour did poorly in 2017 (although they include Labour losses like Mansfield and Walsall North). Nonetheless, the great majority of the battleground seats voted Leave in great numbers than England as a whole and 17 have Leave votes of 60 per cent or more.

The Conservative pushback will include some they surprisingly lost such Canterbury, and Kensington, but are often very similar types of seats to Labour’s targets.

While the ‘two-party system’ re-asserted itself in 2017, it appears increasingly a competition of different social values and less of a class divide. The divergent pattern of swings since 2005 – to Labour in metropolitan areas and university constituencies, and to Conservatives in smaller towns and working class areas – reinforces this interpretation. Nonetheless, it cannot yet be clear whether this is a set trend: for the centre-left vote to become increasingly concentrated in cosmopolitan areas and for the right to gain ground in white working class areas; or an aberrant election result, after which voters will snap back to their previous patterns. Nor is if clear whether Labour has created a strong new coalition for liberal, redistributive, interventionist politics, or whether its unexpected success came from disparate groups of voters thrown together by the unique circumstances of the 2017 election.

What is clear is that next election will be decided primarily in seats that sit on the cusp of that clash of social values. These are largely the towns and smaller cities (often with a chunk of rurality too) outside the metropolitan cities (and mostly not covered by new combined mayoral authorities). Success will go the party that can most successfully reach beyond its current base. Whether that means changing each party’s message, at the risk of alienating its current vote, or working harder to bring new voters over to its current message, will preoccupy party strategists and determine who wins.