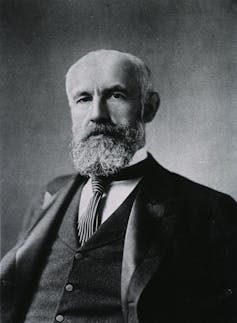

Only children get a bad rap. They are often perceived as selfish, spoiled, anxious, socially inept and lonely. And my profession, psychology, may be partly to blame for these negative stereotypes. Indeed, Granville Stanley Hall, one of the most influential psychologists of the last century and the first president of the American Psychological Association, said that “being an only child is a disease in itself”.

Thankfully, we have made some amends since then. The most recent being a study of almost 2,000 German adults which found that only children are no more likely to be narcissistic than those with siblings. The title of the study is “The End of a Stereotype”.

But many other stereotypes remain, so let’s look at what the scientific research says.

If we look at personality, no differences are found between people with and without siblings in traits such as extroversion, maturity, cooperativeness, autonomy, personal control and leadership. In fact, only children tend to have higher achievement motivation (a measure of aspiration, effort and persistence) and personal adjustment (ability to “acclimatise” to new conditions) than people with siblings.

The higher achievement motivation of only children may explain why they tend to complete more years of education and reach more prestigious occupations than people with siblings.

Some studies have found that only children tend to be more intelligent and have higher academic achievement than people with siblings. A review of 115 studies comparing the intelligence of people with and without siblings, found that only children scored higher on IQ tests and did better academically than people growing up with many siblings or with an older sibling. The only groups that outdid only children in both intelligence and academic achievement were firstborns and people who had just one younger sibling.

It is important to note that the difference in intelligence tends to be found in preschool children but less so in undergraduate students, suggesting that the gap decreases with age.

The mental health of people with and without siblings has also been examined. Again, findings show no difference between the two groups in levels of anxiety, self-esteem and behavioural problems.

It has long been suggested that only children tend to be lonely and have difficulties making friends. Research has compared peer relations and friendships during primary school between only children, first-borns with one sibling and second-borns with one sibling. Findings show that only children had the same number of friends and of the same quality as children in the other groups.

Taken together, these findings seem to suggest that having siblings does not make a big difference in shaping who we are. In fact, when there are differences, it seems that it may be even better not to have siblings. So why might this be the case?

In contrast to children with siblings, only children receive their parents’ undivided attention, love and material resources throughout their lives. It has always been assumed that this brought negative consequences for these children because it made them spoiled and maladjusted. But it could also be suggested that a lack of competition for parental resources may be an advantage for children.

Given that the number of families with only one child is increasing across the world, perhaps the time has come to stop stigmatising only children and condemning parents who choose to have only one child. Only children seem to be doing absolutely fine, if not better, than those of us who have siblings.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. The original article was written by Dr Ana Aznar, Lecturer in Psychology. Read the original article.

Press Office | +44 (0) 1962 827678 | press@winchester.ac.uk | www.twitter.com/_UoWNews

Back to media centre