In our latest blog post, to mark Black History Month, Dr Christina Welch unearths the contribution of indigenous and enslaved African knowledge systems to the St Vincent Botanical Garden under Dr Anderson (1785-1811). Thanks to a collaborative project, after more than 200 years, the Garden has access to its history.

This month, the pop-up exhibition 'Unearthing the Hidden Stories of the St Vincent Botanical Garden' goes to the printers.

The pop-up exhibition is the public engagement output of an Arts and Humanities Research Council Hidden Histories of Environmental Science funded project, led by Dr Christina Welch. The project has brought together a collaborative partnership to unearth the contribution of indigenous and enslaved African knowledge systems to the St Vincent Botanical Garden between 1785 and 1811 when a Scottish naturalist, Dr Alexander Anderson, was superintendent.

The St Vincent Botanical Garden has a long and complicated history. It is the oldest botanical garden in the Western hemisphere, with its establishment dating to June 1765, two years after St Vincent was ceded to the British as part of the Treaty of Paris in February 1763.

Originally established to provide medicinal plants for the military to help the British troops stay healthy enough to retain control of the colonised island, six acres of military land was set aside for the Garden, and Dr Young, the first superintendent and the island's miliary surgeon, was tasked with obtaining information from indigenous peoples and enslaved Africans on the island who "dealt in cures" even if this had to be paid for and was "against [his medical] craft." From the off, there was a distinction made between the British medical knowledge, the medicinal know-how of local people.

In 1785, the St Vincent Botanical Garden passed to Alexander Anderson (1748-1811), a Scottish surgeon and botanist. Anderson was a man of his time; educated, inquisitive, and keen to make a name for himself. Travelling widely in the Caribbean, he recorded plants new to western science introducing many into the Garden, documented the uses of various plants and exchanged observations, information and plants with many other botanists of the time. His letters, dried and pressed plant specimens, plant catalogues and Caribbean natural histories, are held in London by the Linnean Society, the Natural History Museum, the Royal Botanical Gardens Kew and the National Archives. These have been mostly unavailable to the St Vincent Botanical Garden and Caribbean scholars as access has required an in-person visit.

This project, however, has digitised the Anderson archives held by the Linnean Society and the Natural History Museum, including his 1,000-page plant catalogue known as the Hortus St Vincentii, which details the plants growing in the Garden in 1800, and includes a number of botanical illustrations. Several of these are by John Tyley, a young self-taught African-Caribbean naturalist who unusually for this time signed his work. Digitisation of Anderson's Caribbean natural histories and his details of plants growing in the Garden will allow global online access to these important historic resources for the first time.

The project has also interrogated the digitised archive against wider material; letters sent by Anderson held in the archive of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, and receipts relating to Garden and further plant catalogues held at the National Archive. The entire Anderson archive has now been analysed to detect and document the contributions made by the indigenous and enslaved African peoples whose knowledge and physical labour fed into successful development of the Garden and western scientific knowledge more generally. This has highlighted how late-18th & early-19th century concepts of race, class and privilege marginalised the contributions of peoples vital to the development of the Garden.

Significant findings include that Anderson deliberately redesigned the Garden when he took it over to follow the gardening practices of enslaved African provision grounds. He noted in a letter dated June 1786 that the British and European practice of clearing land was "ridiculous" leaving just dry earth. Whereas the enslaved African provision grounds were "filled with all kinds of vegetables in the greatest perfection". Using this system, the Garden grew from around 60 plant species in 1785 to over 1,300 by 1806.

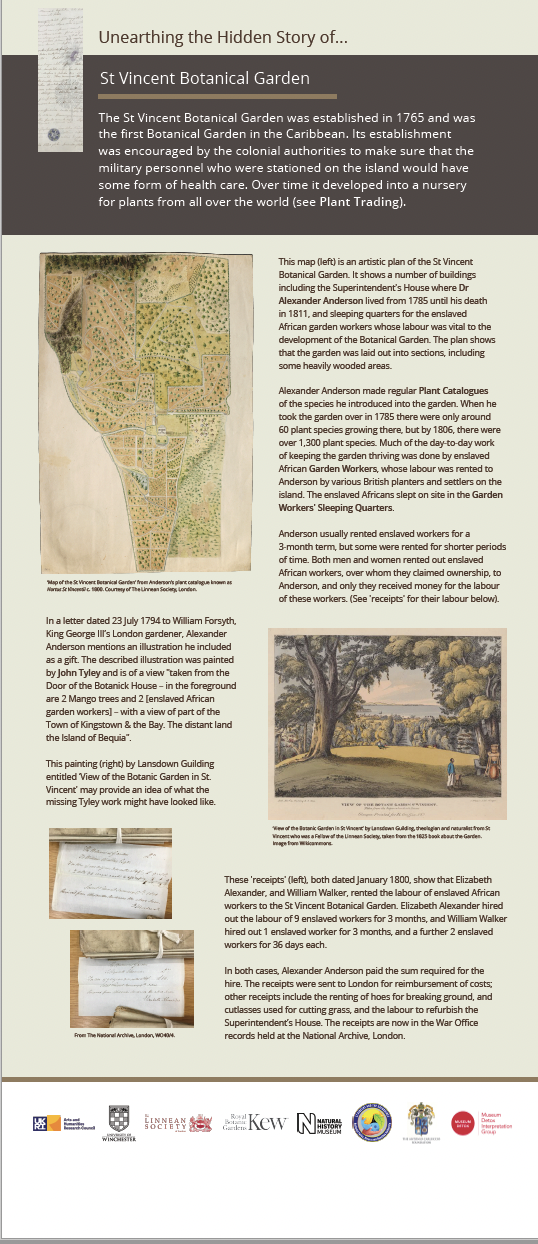

However, as well as drawing on the gardening knowledge of enslaved Africans who worked the plantations on the island, he used their physical labour too. An artistic illustration of the Garden shows a number of sleeping quarters for the enslaved African men who were tasked with the manual duties that ensured the Garden thrived. These included making boxes to ship plants and plant specimens to England, the making and repairing of fences to keep the Garden enclosed and responsibility for gardening including weeding, hoeing, digging and cutting grass with cutlasses, to keeping the Garden tidy and productive. They also carried items to and from the Garden to the port, which was about two miles away; this included transporting boxes of plants, including the famous Breadfruit, from Captain Bligh's ship HMS Providence in January 1793 - a sucker from one of these Breadfruit is still in the Garden today.

The pop-up exhibition will be in the Wycombe Museum from mid-November 2022 to mid-February 2023, and from there will go to the Dundee Botanical Garden. A set of boards will also go to the St Vincent Botanical Garden, which has also been gifted scans of the Anderson manuscripts held by the Linnean Society. The Garden in St Vincent has been involved in the project from the outset with the text for the exhibition banners being agreed with them.

Thanks to this project, after over 200 years the St Vincent Botanical Garden has access to its history.

The project is a collaboration between The University of Winchester (Dr Christina Welch, Dr Gabby Storey), The Linnean Society (Dr Isabelle Charmentier and Andrea Deneau), The Royal Botanical Garden Kew (Dr Bob Allkin, Kristina Patmore and Tiziana Cossu), The Natural History Museum (Dr Jovita Yesilyurt), the Antonio Carluccio Foundation (Prof Niall Finneran), the Museum Detox Interpretation Group (Daniella Briscoe-Peaple), and the St Vincent Botanical Garden (Rodica Tannis-Simmons, Andrew Lockhart and the team at the National Parks, Rivers and Beaches Authority). Thanks also go to His Excellency Cenio Lewis, High Commissioner in London to St Vincent and the Grenadines, Nicola Redway of the Bequia Heritage Foundation, Dr Julie Kim of Fordham University, and the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Photo top and thumbnail on landing page show DR Christina Welch on a research trip to the St Vincent Botanical Garden.

Press Office | +44 (0) 1962 827678 | press@winchester.ac.uk

Back to media centre