Gordon McKelvie, Senior Lecturer in Medieval History at the University of Winchester, argues that history lecturers need to see the Bibliography of British and Irish History’s (BBIH) as more than a convenient tool for updating reading lists. Using the example of revolts through English history, this blog shows how BBIH data can frame classroom discussions about wider historiographical trends.

The Bibliography of British and Irish History’s (BBIH’s) immediate value for teaching is self-evident. A comprehensive and regularly updated bibliography of everything relating to the histories of Britain, England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. It can be used for creating reading lists and is an obvious resource to point prospective dissertation or research students towards, provided they are working on the British Isles. As teachers, we can, however, do more with BBIH than simply email the link to our students or quickly use it each year to make sure we’ve not missed anything new before the onslaught of semester.

BBIH is more than a list of publications: it is a database that can provide concrete data from which to provide insights into trends in historical research. Such data can be a useful starting point for understanding the wider historiographical trends in British history. The ever-increasing demand in British universities for degrees, and those of us teaching them, to demonstrate the employability skills our subject provides means that we need to grab any opportunity to provide students with the ability to discuss data. Yet, in a world in which ‘data-driven’ decisions is all the rage, we must remember that data is the starting point of any discussion, not the end point.

This point is best illustrated by some keyword searches under ‘Search anywhere’ for understanding popular protest, one of my favourite topics to teach. At present a ‘Search anywhere’ search provides a more comprehensive list of relevant materials from the 660,000+ references BBIH holds because the BBIH subject tree was introduced in 1992. Although an increasing number of publications published before 1992 include BBIH subjects, this work is ongoing.

For those of us interested in medieval revolt, we are living through a truly golden age of scholarship with new publications emerging on an almost monthly basis for almost every corner of Europe. Of course, many of these publications fall beyond BBIH’s scope since many focus on continental Europe. Yet, even when focused on England (and this work is overwhelmingly focused on England as relevant searches on BBIH yield very little for Scotland, Wales, and Ireland) BBIH allows some discussion over la longue durée.

Often the phrase ‘medieval protest’ or ‘peasant revolt’ instantly take people to one evident: the revolt of 1381. As a historian interested in popular protest more generally, it can sometimes irk to have to remind people that other revolts did happen, but the BBIH gives us some initial reasons why. The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 is by far the best studied popular protest in British History. The BBIH currently has 153 items listed about the revolt.

The next major uprising in medieval England, that of Jack Cade in 1450, only has 26 items. A note of caution should be made on taking these figures at face value. Cade’s revolt is covered in many histories of Henry VI’s reign or the Wars of the Roses which are not included in the 26 items listed. Moreover, Ralph Griffith’s unrivalled 1981 study of Henry VI’s reign dedicates a full chapter to Cade’s rebellion but understandably, given the book’s sheer breadth of coverage, does not appear in this list of 26 items. The same can be said about the Peasants’ Revolt, to which Nigel Saul dedicated a full chapter in his biography of Richard II—still the go-to text on the reign—but which does not come out in a keyword search for the revolt.

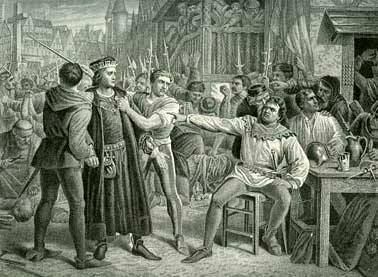

Jack Cade's Revolt depicted by artist Charles Lucy

Keyword searches are not comprehensive in identifying every single occasion in which a revolt was discussed. It was not the objective of the BBIH to cover every index item of every publication. We need to remember the original reason for collecting data rather than the different purposes we might want to use it for. Nevertheless, they help produce statistics that can frame discussions. This example can also be used as a reminder to students to get off their laptops and online searches and go to the physical book on the shelf. The art of wading through contents and indexes pages should never be lost.

Looking beyond the Middle Ages, the Peasants’ Revolt stands out in the long-term history of England. Again, some BBIH keyword searches illustrate this point nicely. The 153 items on the 1381 revolt are significantly higher than many famous later protests. To name the most prominent: the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536 (47), Kett’s Rebellion in 1549 (33), the Monmouth Rebellion in 1685 (67), the Gordon Riots in 1780 (39), the Peterloo Massacre in 1819 (96), and Captain Swing Riots in 1830 (67).

The figures presented here were taken from various searches in November 2024. If you are reading this in a few years, the numbers may be larger. Indeed, we can question how precise these figures are, but this would miss the bigger point: the Peasants Revolt of 1381 is the instance of popular unrest that has attracted more interest than any other in English history. This surely says something about longer term trends in the writing of history? Aren’t these trends something that we need to get our students to think about?

History is about debate, not just about the past but about how people have interpreted the past. What people choose to study and write about is illustrative. Was the revolt of 1381 genuinely the most significant revolt in English history? Alternatively, does it have so many sources that there are always some new documents to pour over? Or, is it simply the case that any historian working on the later middle ages feels the need to write something about the Peasants’ Revolt? Is there a tendency to reinvent the wheel, looking at a well-trodden, but sexier, revolt rather than focusing on another revolt?

Of course, there is no definitive answer to these questions. One possible reason may be the objectives of the peasants in 1381. Most accounts indicate that an end of serfdom was front and centre of rebel demands. In essence, they wanted to change the social order of medieval England. Historians tend to emphasise that serfdom was on the wane anyway and no serious historian would look to 1381 for the roots of universal suffrage or liberal democracy.

The medieval event that is often mis-interpreted with an eye to modern institutions is Magna Carta of 1215. Here, a group of barons imposed a charter on King John, demanding reform of government and equality under the law. The charter’s emphasis on justice does chime with modern sensibilities, but this was an aristocratic revolution rather than a popular one. Here again, BBIH is good for a comparison. At present 353 works have been published on Magna Carta: more than double that of the Peasants’ Revolt.

Are these figures significant? Do they show that historians of England are ultimately more interested in the aristocracy than the peasantry? Are these even fair questions? I, for one, do not know the answer. The one thing I can say is that the BBIH prompts us to think about them.

This brief discussion I hope will give readers some food for thought and ideas about how data drawn from the BBIH can be the starting point, and certainly not the end point, for wider reflections on how historians have written about the British and Irish past.