Reading for pleasure is globally recognised as having a positive impact on a huge range of social issues from poverty to mental health. Yet in England alone, it is estimated that 36 per cent of people don’t read regularly. On World Book Night books are given out across the UK through prisons, homeless shelters, hospitals, colleges and libraries with a focus on reaching new readers. This year, organiser The Reading Agency is working more closely with care homes, youth centres and mental health groups amongst others: an approach which resonates with Winchester’s values of inclusivity and social justice.

To mark this year’s World Book Night, University of Winchester academics based in the Department of English, Creative Writing and American Studies each recommend a book that has a special meaning for them. Read their recommendations and perhaps be inspired to pick up a copy.

Dr Gary Farnell

If we were celebrating World Book Day, then Ulysses – James Joyce’s novel about a day in the life of Dublin – might be a book to blog about. But to mark World Book Night, it’s right to celebrate Finnegans Wake . . . the great Book of the Night in world literature.

Written, again, by James Joyce, we might say that what Ulysses is to the day, the Wake is to the night, comprising a dream running through a single night. Often regarded as a ‘difficult’ work, the Wake is composed in a strange sort of dream-language. Ulysses is famous for its use of ‘stream of consciousness’, to register the inner life of its protagonists: what is used in the Wake is streams of un-consciousness.

So the contents of this work may not be easy to summarise, except to say that it offers a retelling of the myth of the Fall of Man. Published in 1939, and due to its working against authoritarian modes of sense-making, it has been hailed as anti-fascist. Indeed, as a work of art it is comparable to Picasso’s Guernica.

'If This Is a Man' by Primo Levi (1947)

Dr Ruth Gilbert

When I was asked to come up with just one recommendation for World Book Night, I thought it would be impossible. I’ve read a lot of great books over the years. But one stands out: Primo Levi’s memoir, If This is a Man. It was first published in Italian in 1947. It didn’t sell many copies initially but later it was translated into English and has been in print ever since. I teach it on a course for English Literature students so I read it again every year. And, with every re-reading, Levi’s account of his time in Auschwitz has a profound impact.

Levi was an Italian Jew. He studied chemistry and in his early twenties he joined the anti-fascist resistant movement. He was arrested by the Nazis in 1944. He tells his story with a sense of understated precision and this makes his writing all the more powerful and affecting. He describes some unimaginable experiences. The Nazis tried to strip the prisoners of everything that made them human – but Levi shows how, in such dark times, seemingly small moments of connection reminded him of his own humanity.

Levi wrote about his experiences so that people wouldn’t forget about the atrocities of the Holocaust. Reading his work reminds me of how we all need to remember our humanity. Now more than ever.

'White Noise' by Don DeLillo (1985)

Dr Matthew Leggatt

While, perhaps, the kind of book you either ‘get’ or ‘don’t get’, I would fully recommend American writer Don DeLillo’s 1985 novel White Noise. As probably the most frequently read book by this iconic contemporary American writer, White Noise offers a true reflection of the author’s enigmatic and highly ironic postmodern style.

It is a biting satire of contemporary ‘reality’, from the characters’ obsessions with the Television, celebrity, and the mysteries of supermarket shopping, to its musings about our fear of death and our obsession with its demystification. Having gone to University to study English fresh out of school, this novel, alongside Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, is the book that opened my eyes and began to shape my fledgling political consciousness. It made me aware of new ways in which to see and critique the world around me. While not necessarily a page turner, every page, it seemed to me, crackled with the energy of a new idea or insight, and the dialogue in this book is expertly tuned to capture the absurdist nature of life at the end of the twentieth century (and beyond).

If you’re looking for romance, empathy, or thrilling narrative then this is probably not the book for you, but if you’re looking for insight, wit, and something that’ll keep you thinking for years after you’ve read it, then try White Noise.

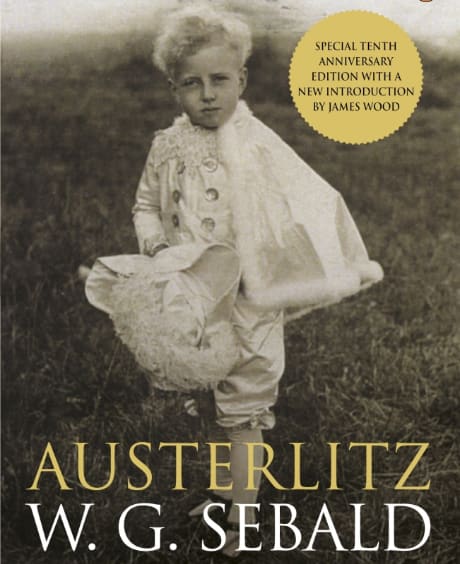

'Austerlitz' by W G Sebald (2001)

Dr Daniel Varndell

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein argued that the definition of a ‘self’ was a picture of an organism held by that organism – a ‘picture’, wrote he, that held us captive and from which we could not escape: ‘for it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us inexorably.’ The search to find one such ‘picture’ is what drives the eponymous protagonist of W G Sebald’s final novel, Austerlitz – published just before his untimely death in 2001.

It is his magnum opus, a triumphant culmination of his earlier works, including the stylistic blending of fiction and fact (Vertigo), the discursive style reflecting peripatetic themes and narratives (The Emigrants), travelogue (The Rings of Saturn), and, of course, the attempt at rapprochement with Europe’s fascist past. It is a reflective novel charting the journey of a man looking to unlock the mystery behind his arrival in England on the Kinder-transport from Czechoslovakia in 1939, aged just five, his parents lost somewhere in the foreignness of a forgotten time.

Ultimately, the aporia of Austerlitz’ story reflects the impasse of a post-fascist Europe struggling to come to terms with its recent past, a past still perturbing the ‘picture’ today. Austerlitz’ struggle to discover his lost origins is, then, finally our own. It is a struggle without which we must surely find ourselves – we twenty-first century Europeans – turning away, to paraphrase Sebald, from both self and world.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the University.