David Slater, a British wildlife photographer, travelled to Sulawesi in Indonesia to take pictures of the island’s crested black macaque population in 2011. Slater wanted to capture images of the macaques in a bid to publicise their plight. The Macaca nigra is critically endangered and fighting for its survival; the macaque population has plummeted by 90 per cent during the last 25 years. The macaque’s habitat has been destroyed by human encroachment and the monkeys are killed as pests for raiding crops of local farmers. They are hunted as bushmeat and trapped to keep shackled as pets. This is all despite the Macaca nigra being a protected species.

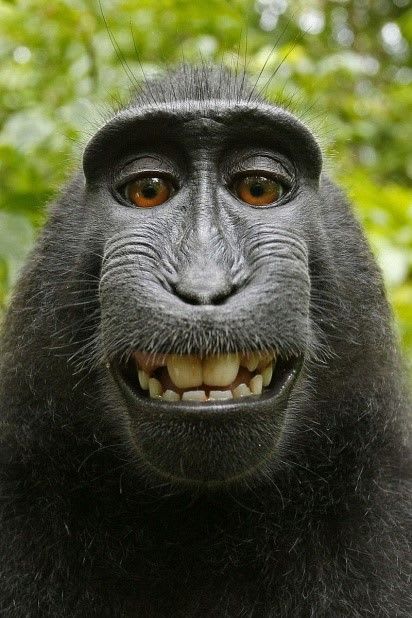

Slater describes how he spent three days assisted by a local guide with the gregarious macaques. Despite the monkeys trusting Slater enough to groom him, they wouldn’t allow him to take a close-up photograph. Slater configured the settings on his camera for a close-up shot and the macaques began to manipulate the camera and ultimately took the infamous monkey selfies at the heart of the Naruto versus David Slater court case.

Slater published the monkey selfies through Carters News Agency in 2011. In the same year, the blog site Techdirt claimed that Slater did not own the copyright, since the macaque had taken the photograph. Wikimedia also published the monkey selfies, and both declined Slater’s requests to remove the images, arguing that the photographs were in the public domain. Slater reported that he had earned £2,000 from the photographs until that point but when Wikimedia published the images his income dried up. Experts in copyright law have been divided on the issue of whether Slater owns copyright. Whereas some agree that there is no copyright claim, others argue that Slater's creative input is sufficient for legal ownership.

In 2014, Slater included the macaque selfies in his book Wildlife Personalities, published by Blurb Inc. In September 2015, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) filed a suit in California against Slater and Blurb Inc. PETA argued that it was the macaque in the selfies, who they named ‘Naruto’, who was the legitimate copyright holder. PETA would administer the proceeds from the sale of Naruto’s images to protect the local macaque population and its habitat, without compensation. The case was dismissed in January 2016 by a US judge, who reasoned that Congress and the presidential office had not authorised that non-human animals such as macaques have legal standing to sue humans. PETA appealed against the District Judge’s decision and the case was heard on 12 July 2017 in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal in San Francisco.

In its opening brief PETA, acting as Next Friend of Naruto, advanced five arguments in support of its case:

It is easy to dismiss the monkey selfies case as a publicity stunt of a controversial animal rights organisation. However, as David Favre, a Law Professor at Michigan State University, has stated, the monkey selfies case is at the cutting edge of animal law. In the US, there is a growing movement amongst a band of respected legal scholars to recognise personhood, and associated legal rights, for nonhuman persons. For instance, the Nonhuman Rights Project (NHRP), led by the Stanford legal scholar Steven Wise, has been trying cases in common law under a writ of habeas corpus to recognise chimpanzees as legal persons and not merely legal things. Wise and his team, based on evidence supplied from primatologists such as Jane Goodall, argue that chimpanzees, based on their highly-developed cognitive capacities, are autonomous and self-determining beings in the same way that humans are. The recognition of chimpanzees as legal persons would lead to ascribing fundamental rights to them including the right to bodily liberty. Similarly, PETA sued SeaWorld for enslavement of killer whales under the US 13th Amendment. PETA, which lost the case, argued that orcas were of a sufficient level of cognitive development to ascribe personhood, thus had legal rights such that they could not be enslaved in SeaWorld aquaria.

Returning to the case at hand, PETA rightly argues that the proceeds of the monkey selfies could provide great benefit to Naruto and his fellow Indonesian crested black macaques. However, the fundamental issue of importance is whether non-human animals can be recognised in the courts as legal persons. If macaques and other species of advanced cognitive development can be recognised as persons – for instance by holding copyright – then they can also be seen to hold legal rights to protect more fundamental interests, for instance the right to bodily liberty, generating immunity against suffering, being killed and being held as property of humans.

In the UK, with a greater focus on improving animal welfare, we may see such discussion about animal rights as rather radical. However, consider the Great Ape Project, pioneered by the philosophers Peter Singer and Paola Cavalieri. The Great Ape Project seeks to extend fundamental rights to chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans, based on their higher cognitive capacities. The argument, in effect, is that great apes are so cognitively similar to humans that we should grant them rights that are similar to humans. So, how do we treat great apes in Great Britain? Well, despite the four million experimental procedures on a range of species in the UK in 2016-17, we have not experimented on great apes in the UK since 1998. In effect, morally at least, British society has granted great apes the right to not be harmed in scientific and medical advancement, based on their biological and cognitive similarity to human beings.

To end, how should we judge the Naruto versus Slater case? Does Naruto have a moral right, defined as a valid claim to protect an important interest, to copyright? Arguably, Naruto has a very substantial interest in the copyright, given the decimation of his population over the last 25 years and continued threats. Copyright grants access to the financial proceeds of the monkey selfies, which can be administered by PETA to safeguard the macaque's habitat and the troop's welfare. Did the monkey contribute to authorship of the photograph? Naruto is both the subject of and to a substantial degree the producer of the monkey selfies. Hence, Naruto has not only an interest in copyright, but to a significant extent a valid claim to it. If copyright law is designed to protect the financial and other benefits that accrue to those who produce works of art, then in this case, arguably, Naruto has at least some claim on the copyright.

Have your say

Have something to add or would like to share your thoughts? Tell us in the comment section below.

Dr Steven McCulloch has also contributed General election 2017: what do political party manifestos pledge on animal welfare policy? to the University blog.