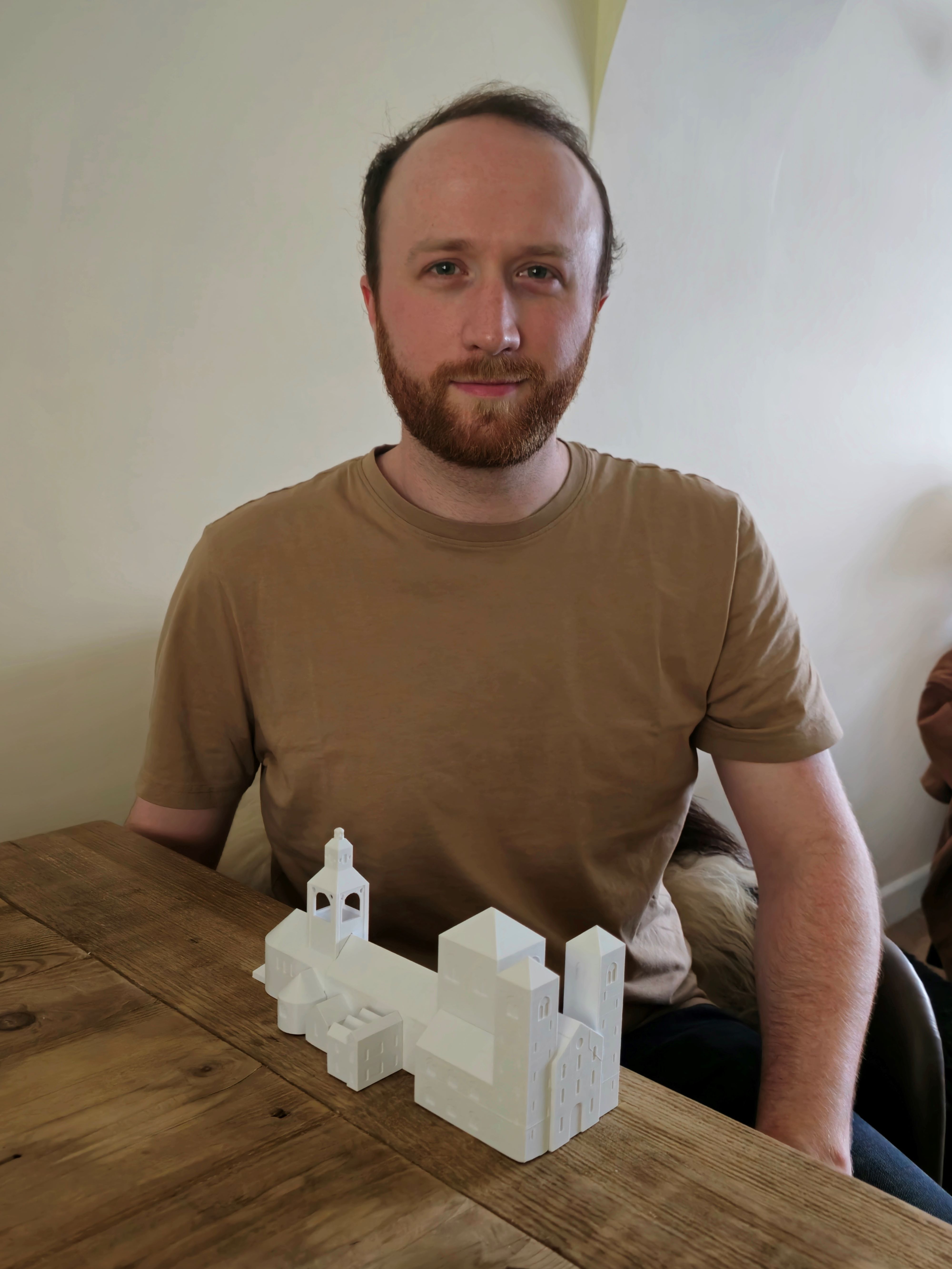

A History student from the University of Winchester is rebuilding the past with the aid of 3D printing and magnets.

Jacob Newbury believes the best way to understand how ancient buildings were originally constructed and added to through the ages is to build one yourself.

As many historic buildings are made up of different sections from different eras, Jacob came up with the idea of designing multi-part 3D printed models with magnets inlaid into the walls so they can be snapped together.

He believes these multi-part models can be a great learning aid from primary school right up to university level.

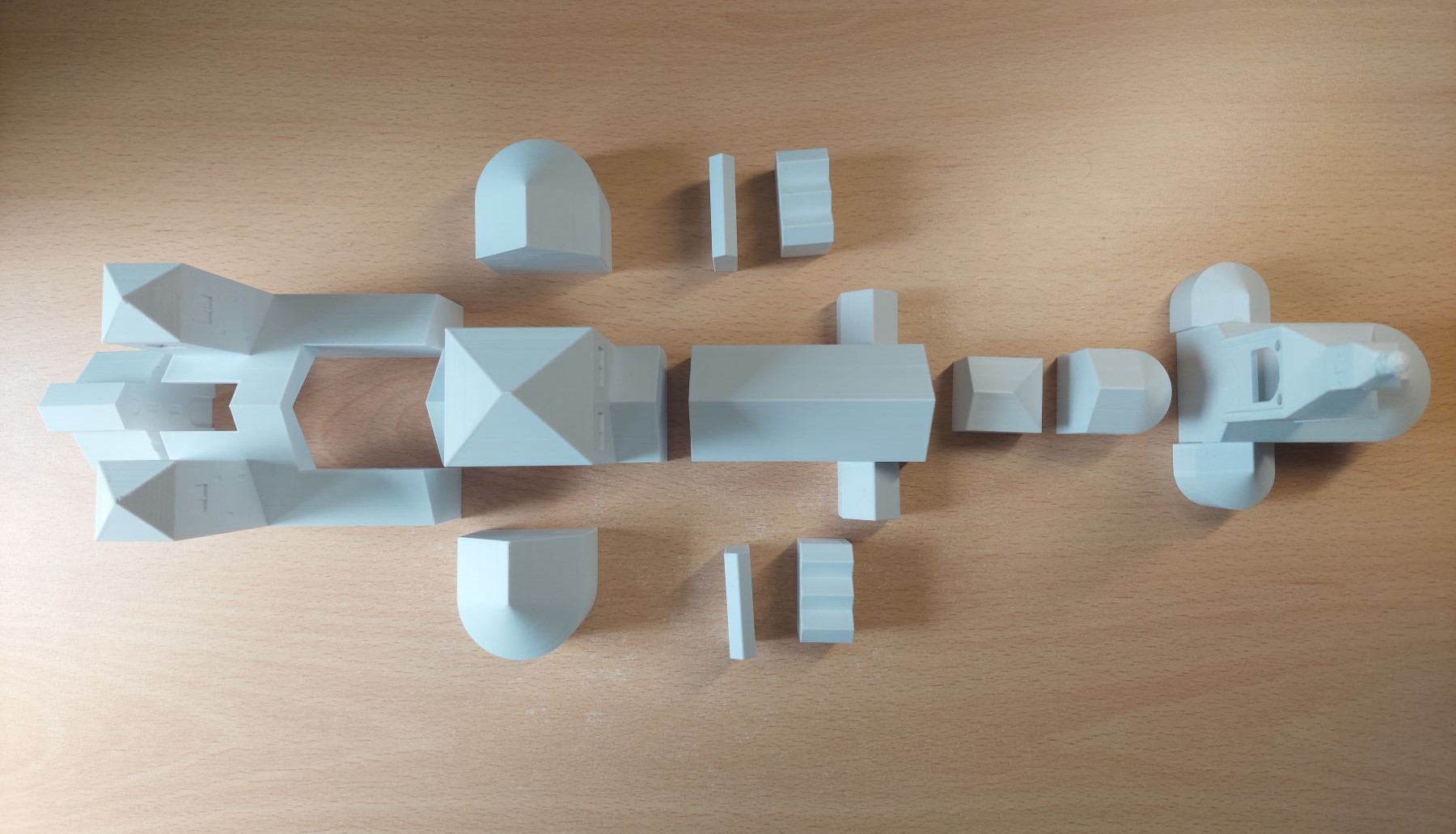

The sum of its parts...Jacob's Minster model exploded

Jacob describes how he used Winchester’s Old Minster as a case study in an article , just published in Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, co-authored by Ryan Lavelle, Professor of History at the University of Winchester

“By using magnets in these models, we've shown that complicated multi-part buildings (which is pretty much all historical buildings) can actually be easily produced for a wide audience to intuitively understand,” said Jacob.

“Ultimately, the first-hand understanding that can be gained from putting these parts together is far more helpful than other forms of reconstruction like that of CGI drawings or artwork.”

Jacob says the study of ecclesiastical buildings lends itself particularly well to this application as there are often published plans available and churches have often undergone multiple changes to their architecture and use during their lifetimes.

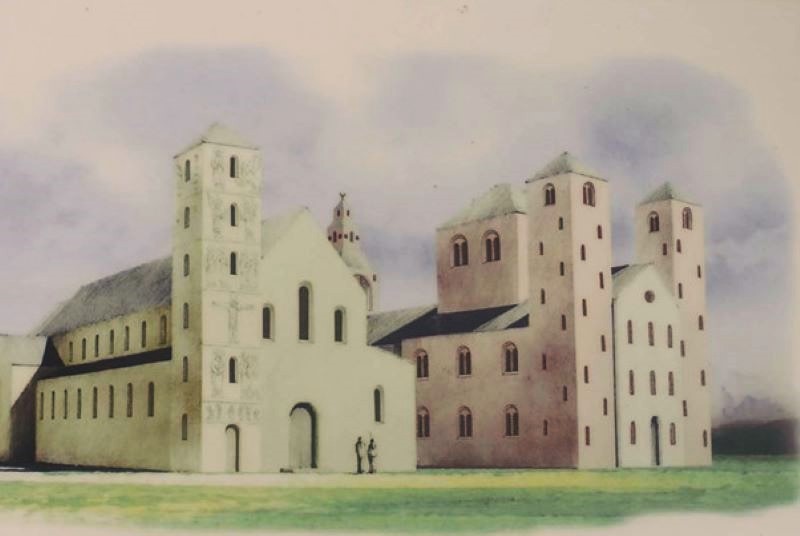

Winchester's Old (right) and New Minsters (Image: Simon Hayfield, Winchester Excavations Committee)

Winchester's Old (right) and New Minsters (Image: Simon Hayfield, Winchester Excavations Committee)

The Old Minster, whose outline can be seen in the grass beside Winchester Cathedral, was excavated in the 1960s and has been the subject of several studies and visualisations.

In his paper Jacob discussed the similarities between the Old Minster and other lost religious buildings from the time (which have been similarly excavated) such as the original Canterbury Cathedral and Cirencester Minster as well as surviving structures - Boarhunt church in Hampshire and the church of St Laurence in Bradford-upon-Avon.

Professor Lavelle, who has used the minster model successfully in his teaching at the University of Winchester, said: “It’s great that Jacob has used his expertise and energy to develop a new way of presenting multi-phase buildings, applying it here to such a famous rendition of Winchester’s early cathedral. Jacob’s model has given a new way of looking at -- and feeling -- Winchester Excavations Committee’s reconstruction of the Anglo-Saxon church.”

.jpg) Jacob's array of models of ecclesiastical buildings

Jacob's array of models of ecclesiastical buildings

Jacob’s journey

Jacob, 25, from Horley in West Sussex, left school with the ambition of following a career in computer science but an interest in genealogy led a to wider interest in history.

After his A-levels, Jacob worked freelance doing digital photo restoration and colourisation.

During the covid pandemic Jacob taught himself how to read medieval documents and to transcribe and translate medieval Latin.

“I've always been interested in history, but medieval history grabs me. I've been incredibly fortunate to be able to track my family history through the medieval period and I suppose it was doing that research that helped me connect to what once seemed like an unknown period to me and helped make it more tangible,” said Jacob.

He also used lockdown to master 3D modelling.

“I’d got fed up with wanting to manifest something and not having the tools to do so and realised that 3D printing is an incredibly cost-efficient technology and set myself to learning how to use it,” he said.

Having completed his degree in Medieval History, Jacob is about to embark on his doctoral studies at Winchester in September.

Back to media centre