Research being carried out at the University of Winchester could help combat the illegal trade in pangolins, the only mammal to grow scales, by using the latest fingerprinting techniques.

Pangolins have become the world’s most trafficked wild mammal in recent years. Poaching has increased rapidly to meet a growing demand for their scales for use in traditional medicines in the Far East.

Researchers at the University of Portsmouth have been working to recover finger marks from pangolin scales, and exploring how this could identify poachers.

Now the Portsmouth team is being assisted by University of Winchester Forensic Investigation student Rebecca Barnard. She is looking at gel lifts, a technique used to lift finger marks off a non-porous smooth surface.

Winchester Forensics Lecturer Selina Robinson was able to put Rebecca in touch with Portsmouth who have pangolin scales confiscated by UK Border Force which they use in their research.

Third year student Rebecca (pictured) from Canterbury, said: “I’ve always been passionate about animals and conservation and I’m very interested in wildlife forensics.

“Pangolins are at serious risk and were at the forefront of my mind when I came to choosing a topic for my dissertation.”

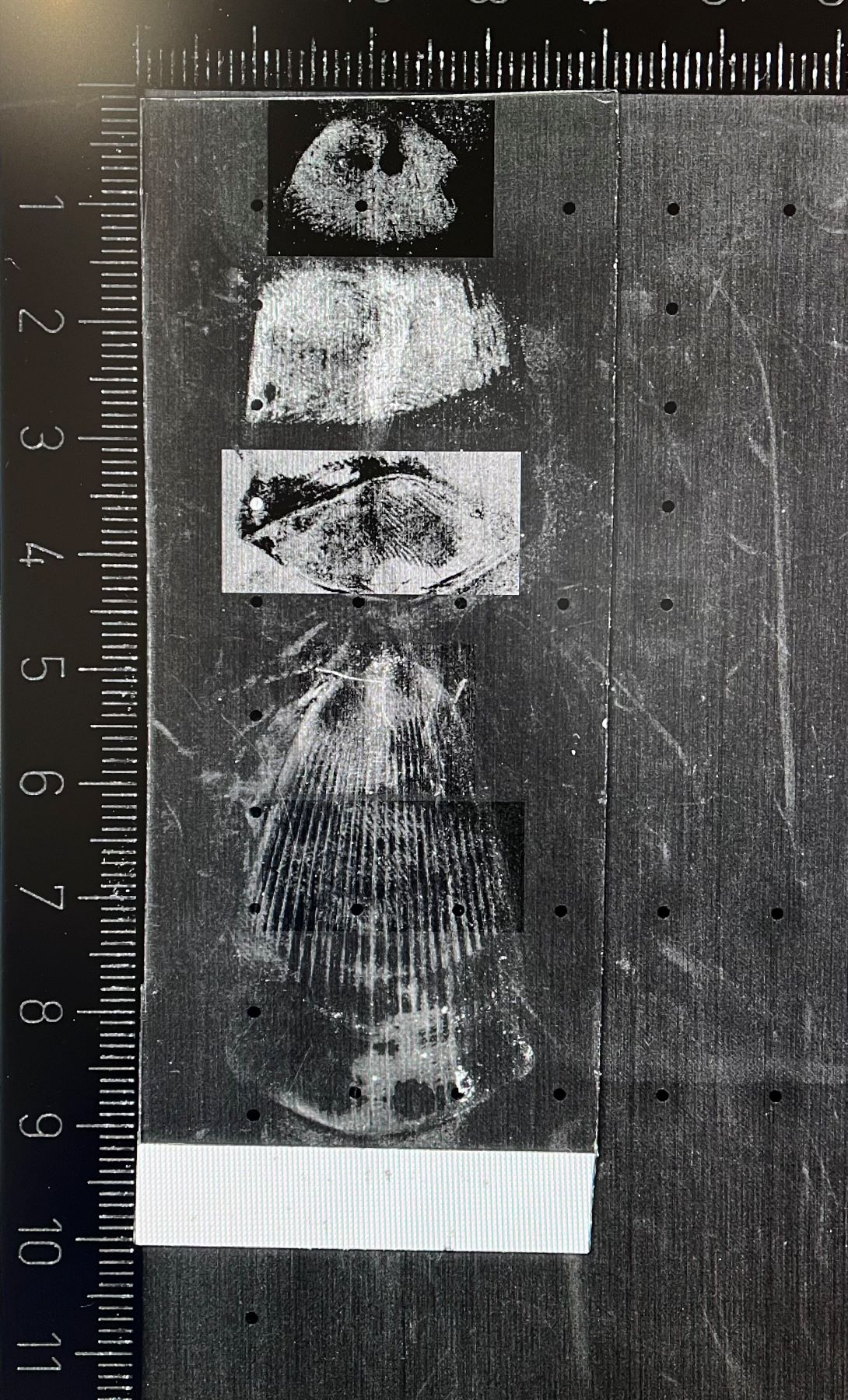

Rebecca’s study focusses on different colour gel lifts - the gel used so far is black and Rebecca will be using not only black but white and clear gel to investigate which gives the best results.

Pangolin scales are made of keratin, the same substance that makes up human hair and fingernails and rhino horns. Gels are believed to be less harmful to the scales than old fashioned powders and chemicals used to detect fingerprints.

Fingerprints lifted from the pangolin scales

Traditionally pangolins were poached primarily for bushmeat and their scales thrown away.

However, in the last decade the prices for scales, skins and the whole animal have soared with Vietnam and China driving demand.

In Chinese medicine the scales are used in a wide variety of treatments, including remedies for skin infections and female infertility. Despite their widespread use is no credible scientific evidence suggesting the scales have any medicinal properties.

All eight species of pangolin, sometimes called scaly anteaters, are protected under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the highest level of international law.

Asian pangolins are estimated to have declined by up to 80 percent in the last 10 years. In the last decade more than 850,000 pangolins were traded illegally.

“It would be great if my work could make it easier to identify the people involved in this illegal trade or even act as a deterrent,” said Rebecca, 20.

Back to media centre