In the week that Boris Johnson became the new Prime Minister and the LibDems chose Jo Swinson as the party's new leader, new research from the Centre for English Identity and Politics (CEIP) has highlighted a challenge to all political parties in responding to a significant group of English voters. CEIP Director Professor John Denham discusses voter attitudes to English issues.

These voters emphasise their English identity: they believe England has interests separate to those of the rest of the UK, they want political parties to stand up for England's interests and they want changes in the way England is governed. Although a minority of all voters in England, they are sufficient in number to determine the outcome of many constituency votes.

The research1 poses difficult challenges for the new Prime Minister and other major party leaders.

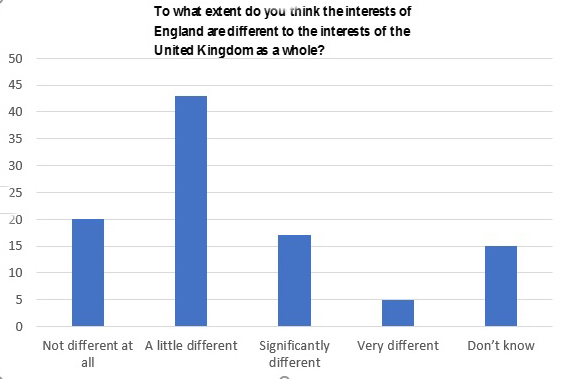

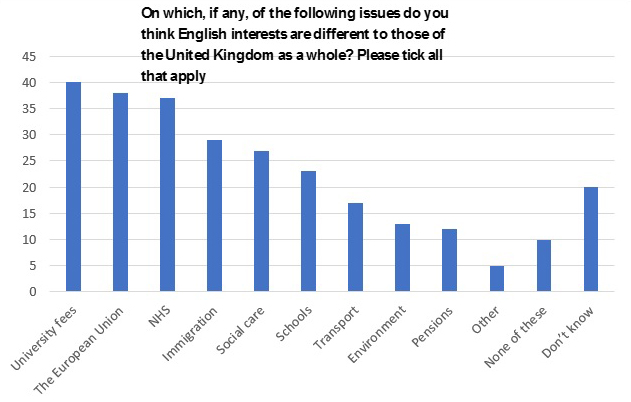

Over a fifth (22%)2 of English voters think England's interests are significantly or very different to those of the UK as a whole. 70% of voters were able to identify at least one issue on which England's interests were distinct, with university fees, the EU, and the NHS being chosen most often, followed by immigration, social care, and schools.

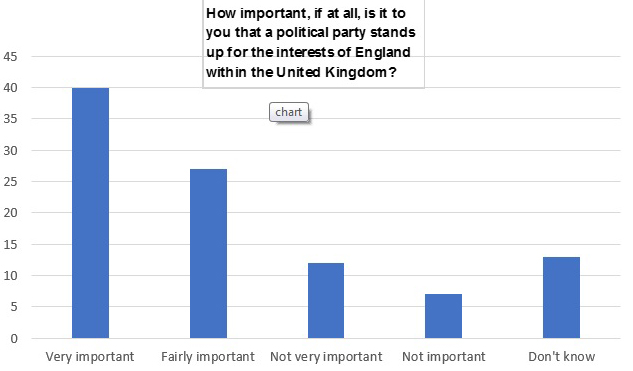

Two out of five voters (40%) say that it is 'very important that a political party stands up for the interests of England within the union', and another quarter (27%) say it is fairly important.

But half of all England's voters were unable to identify a party that 'best stands up for the interests of England'. 30% thought no party did, and 21% didn't know.

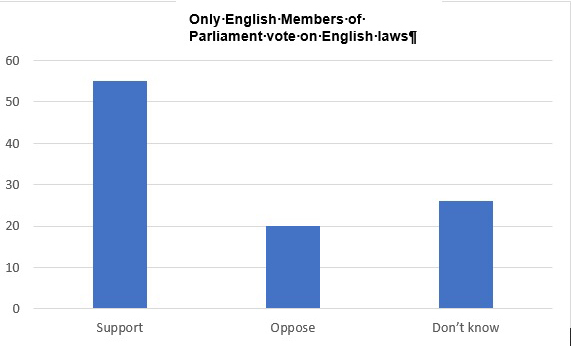

The new poll also shows strong public support for the principle that only English MPs should be able to vote on English laws. 55% supported the change (with 20% opposed) believing that it would improve England's governance.

About half of these thought the change would make England's governance 'much better'3. A plurality of voters also supported an English Parliament, regional assemblies and combined authorities, but none of these options gained more than 50% nor as effective in improving the government of England.

Support for change is strongest amongst older voters and those who emphasise their English identity4 and opposition is strongest amongst those who prioritise British identity. English MPs making English laws is the only change where more 'British not English' voters think it would improve, rather than worsen, England's government.

At the time of the poll, the Brexit Party was most likely to be named as the party that best stands up for England being chosen by twice as many voters (17%) as any of the mainstream parties: Conservatives (8%), Labour (9%) or the Liberal Democrats (8%). However, as recently as 2017, Labour was seen as the best party for England by 31% of voters, with the Conservatives on 24% and UKIP on 9%, suggesting that no party has firmly established itself as the best to represent England.

Party attitudes towards England are obviously only one of many factors influencing voters, but the strength of opinions held by a minority of voters suggests that there are potentially significant gains for a political party that can harness this support. Equally important, parties that appear indifferent or hostile to English interests will face an additional hurdle in reaching the same voters. The challenges are different for each of the parties.

The Conservatives have the highest proportion (85%) of their 2017 voters who want a political party to stand up for England within the union. However, these voters are currently more likely to see the Brexit Party playing that role. Conservative Party members also prioritise Brexit over the union, and believe that devolution has damaged England. If it proves difficult to deliver a Brexit that satisfies these voters and members the new Prime Minister may be tempted to make a more explicitly English appeal . However, this will be difficult without bringing into question the Conservatives' traditional commitment to the union and undermining their MPs in Scotland and Wales.

Although Labour's base is 'less English' than the Conservatives, over half (56%) of its 2017 Remain voters want a party that stands up for English issues. As voters who want such a party but are more likely to be Leavers, older, working class and to identify as English, Labour may need a clear English message to win back lost voters in their key target constituencies. Labour's challenge will be to do this without alienating the more liberal, graduate, and Remain voters in big cities and university towns who swung to support the party in 2017.

The new Liberal Democrat leader Jo Swinson faces a similar dilemma to Labour, with half its 2017 voters wanting a party to stand up for England. The LibDems currently are doing better than Labour and the Conservatives: its 2017 voters are about twice as likely to see the party as standing up for England. Jo Swinson will be aware that it needs to win back English focussed voter support to win back some of their lost constituencies. It was voters in English LibDem seats who switched to the Conservatives in 2015 (giving David Cameron his majority) because they wanted to be sure a minority Labour government would not be held to ransom by the SNP. Whether the decision to brand itself sharply as an unambiguously Remain party puts it out of step with these English centred voters remains to be seen.

This polling evidence suggests that a significant minority of voters identify English interests and issues distinct from the United Kingdom as a whole. They want political parties to stand up for English issues. The same voters want changes to the way England is governed, particularly to ensure that only English MPs can vote on English laws. Each of the mainstream political parties face both opportunities and challenges amongst voters who put English issues first.

It's possible to identify two ways that party strategists might target this support.

Parties could acknowledge concern about England's distinct issues by setting out clearly how their policies for England, particularly on devolved issues, might be distinct from policy in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

They could also commit to far more extensive changes to England's governance than have been considered to date. Of these, moves to extend the current limited 'English Votes for English Laws' to further stages of the Parliamentary process would have most support, but also the widest constitutional ramifications.

Notes

1. Survey of 1470 English residents, 9-10 June 2019, YouGov, commissioned by the CEIP, University of Winchester

2. Don't knows have been excluded from the data in this note

3. Scoring 4 or 5 on a scale from -5 (much worse) to +5 (much better)

4. The survey asked respondents 'which of the following best describes the way you think of yourself':

| English not British | 14% |

| More English than British | 13% |

| Equally English and British | 39% |

| More British than English | 9% |

| British not English | 7% |

| Other/don't know | 9% |

Press Office | +44 (0) 1962 827678 | press@winchester.ac.uk | www.twitter.com/_UoWNews

Back to media centre